Exploring the Blot – Part 2: The Sacred Verse

By Mark Puryear

First published in ORB 209, Summer 2258

In the near twenty years that I have been practicing our beloved religion I have read dozens of works that seek to revive our methods of offering to the Gods and Goddesses. At the same time, I have been performing these blotar, both alone and with groups, using what I could from available materials, and my own intuition. I cannot recount how many times I have written and re-written blot formulae, constantly changing the formats and wording to fit the needs of each particular observance. Some of the books I’ve read were indeed good people within the folkish Odinic movement, while far too many others reach into the morass of new age invention. Although a lot of the folkish works are absolutely useful, it is always at the heart of practicing an ancestral religion like our’s to try to seek the closest possible form of the customs utilized by our ancestors. We sift through the fragments left for us, sometimes agonizingly so, and try to shape the best possible image of how these blotar were performed, then attempt to adapt this to our circumstances today.

Upon researching this topic extensively, it seems that one of the most important factors in developing our rites has gone missing from our modern practice, and that re-awakening these traditions would be a great service to the legacy of our ancestors. Since it is heritage that we are trying to build, it is only right and proper that we keep those aspects of early Northern culture alive and thriving, if it is within our capabilities to do so. If such a revival can be of practical use to us now, then so much the better.

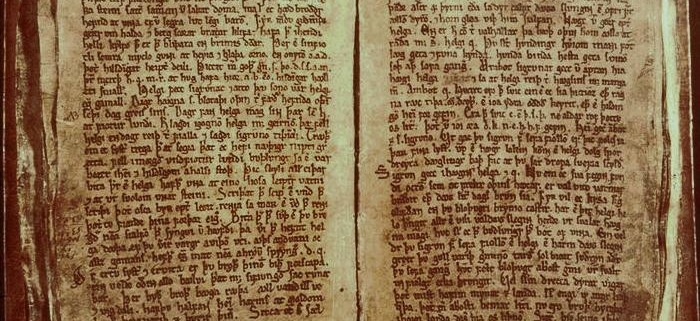

In ancient societies poetry was an incredibly important factor of religious expression, especially in Teutonic Europe where Skaldic and Eddic art forms were highly valued and praised among the folk. In fact, every piece of lore that has survived from the pre-Christian era in this region was written in verse. Therefore, it would be safe to say that this practice was also used in the writing of prayers (boenar) and blotar as well. When we consider the fact that the Hindus, our Indo-European cousins, have retained their sacred verse forms and meters (Anustup, Mahapadapunkti, etc.) in liturgical hymns and prayers for thousands of years, it is easy to see that the same would have been the case for us, had it not been for the Christian invasions.

However, we should not forget that the verse forms themselves have survived in various texts, including the Eddas. We simply do not have a direct relationship between them and actual blot accounts that can be readily seen. I do believe that once we peel away some of the layers of obscurity, that such a connection can be made obvious, which might be able to aid us in setting a standard we can use today. The idea is to create a template by which modern practitioners can write their own rites, using information that we are fairly confident has a traditional foundation.

In the Eddas there are two types of verse that stand out above the rest in terms of using them for ceremonial purposes, although one is but a variant of the other. The first is called “Ljodahattr”, which means “song-verse,” although I believe a more appropriate translation would be “sacred-song-verse.” The word “Ljod” is almost always used in conjunction with prayers, rites, or religiously significant speech. In consideration of this term we must look at the Eddic poems themselves. All of the advisory accounts, the words of the Gods and Goddesses, including Havamal, Sigrdrifumal, Vafthrudnismal, etc. are written using the Ljodahattr meter. In addition, every verse within these poems which contains any sort of prayer or possible prayer, is written in this meter, including the famous “Hail to Dag” found in Sigrdrifumal (str. 3-4):

“Hail Dag!

Hail Dag’s sons!

Hail Natt and Nipt!

Look down upon us

with benevolent eyes

and give success to the sitting!

Hail the Aesir!

Hail the Asynjur!

Hail the bounteous Jord!

Words and wisdom

give to us,

and healing hands in life!”

Some of the alliteration is lost in the translation, but these strophes provide us with an excellent concept of how such prayers were composed. Though this is our longest, most elegant example, there are others (such as Lokasenna 11 and Grougaldr 1) that may also relate to early Odinic prayer. In all of these it is the Ljodahattr meter that is utilized.

In Havamal 145, Odin asks “Do you know how to pray? Do you know how to blot?” in a Galdralag verse, which is a variant of the Ljodahattr. In strophe 141 he has discovered the runes, which are here called Fimbulljodur or “The Great Songs” (“-ljodur” is the plural form of “ljod”), while in Ynglingasaga ch. 6 the Gods are called Ljodasmidir – “The Song-Smiths”. In each case, the word “ljod” is employed, in contrast with the ON “songr” or “song”, which may have been more of a secular expression. It should be noted that in Ynglingasaga ch. 2, the Gods, the Ljodasmidir, are described as priests, furthering the connection of the “ljod” to prayers, since they are their “smiths”. When Odinn, lord of the Fimbulljodur, highest of the Ljodasmidir, asks us if we know how to pray using a form of the Ljodahattr meter, we should recognize this as important, especially considering that he is the inventor of poetry (Skaldskaparmal 2-3) and “speaks everything in verse” (Y nglingasaga ch. 6).

The second most valuable verse form for writing blotar is Galdralag or “Galdr-verse”, whose name should make its significance easily recognizable to Odinists. Here we see, in both cases, a connection with the runes. Galdr is well established as the holy art of runic wisdom and prayer, while above we see the word “ljod” is used to designate both the runes (Fimbulljodur) and sacred meter (Ljodahattr). The utilization of runes in prayer and offering is described in Sigdrifumal 18, where it is stated that consecrated objects have these sigils marked on them, then “all were erased that were inscribed, and mixed with the holy mead, and sent on distant ways.” This strophe is written in Galdralag, and should be compared to the above mentioned Havamal strophe (145), which asks is we know how to use the runes in sacrifice:

“Do you know how to write them?

Do you know how to interpret them?

Do you know how to draw them?

Do you know how to prove them?

Do you know how to pray?

Do you know how to blot?

Do you know how to send?

Do you know how to consume?”

When Snorri Sturluson compiled the Prose Edda, it was not to create a textbook of Odinic lore; this was a secondary benefit. Its primary purpose was to serve as a manual for learning and preserving the poet’s craft of Scandinavia. The work is divided into three sections: Gylfaginning, which presents an overview of the stories and offers some Eddic passages; Skaldskaparmal, which described the use of kennings (poetic metaphors), gives name-lists for various beings, plants, animals and objects, and explains skaldic poetry to an extent; and Hattatal, which describes the verse forms themselves. In understanding this, we can see how vital these poetic customs were believed to be by the inhabitants of Northern Europe, even three hundred years after the conversions.

But why were they so important? Every civilization seeks to develop and maintain cultural institutions that define the inhabitants’ way of life. In order to do this, there must be some sort of record to keep the beliefs of the previous generation alive. Before written texts were created, this lore survived through oral traditions passed down from ancestors to descendants. Poetry is a tool that allows this to happen with less difficulty than prose, simply because the rhythm of meter makes memorization easier. Plus, verse forms allow for particular styles to develop that can become a part of the broader culture, granting each folk a unique system they can call their own. In adapting these ideas to our own practices today, this should certainly be taken into consideration.

With all of this said, we should look at exactly how to compose the Ljodahattr and Galdralag verses. Both of them usually consist of six lines, but not always. Ljodahattr is made up of two half-strophes, in which the first two of the three lines in most cases, have three to six syllables and alliterate with each other. The third line then has four to eight syllables and alliterates within itself. Here is an example from the blot formula I use:

“In feasting we find (5 syllables),

joy amongst friends (4 syllables: “friends”, “feasting”, and “find” alliterate),

hail to Heimdall’s children! (6 syllables: “hail” and “Heimdall” alliterate),

Noble deities (5 syllables)

dancing in the sky (5 syllables: “dancing” and “deities” alliterate),

shine down as we share in kind!” (7 syllables: “shine” and share” alliterate).

The strophe was written for the gothi or gythija to speak, or sing, after the mead consumption. I like to actually sing the verses, since they are in the “song-meter”, which is done with sort of droning tone. Still, others may be more comfortable speaking them, which is perfectly fine. In response to each verse I sing, I join the gathered in speaking a verse of Galdralag. Again, this is a strophe of six lines with three to eight syllables each that alliterate with one another. These use repetition to maintain the rhythm, which becomes a chant, in keeping with the Galdr tradition. This example of the Galdralag verse follows the above in the blotar I perform:

“May our clans be (4 syllables),

kept strong in our union (6 syllables),

devoted are we to you (7 syllables),

devoted are we to the folk (7 syllables),

as Sunna’s rays beam forth (6 syllables),

dedicated are we to our ways.” (8 syllables).

As stated, I have experimented with methods of honouring our deities for many years now, and I must say that the Ljodahattr and Galdralag have been the most efficient tools I have found for this. Not only because these are traditional meters, but also because they simplify the entire process for both the gothi and the gathered folk. I have a standard eighteen verse blot (corresponding to the eighteen Fimbulljodur in Havamal) in which fourteen of these are used every time. For each particular blot a new prayer, consisting of four verses, is used to focus on the event celebrated. This means that once I memorized the fourteen standard verses, I only have to do this with the four of the prayer at each festival. This simplification has actually created a more flowing rite and a greater spiritual experience for myself and the other practitioners. One would have to try this for themselves however.

Verses are easily memorized and the folk can read the rite off a single piece of paper. Since they are not concerned with pouring mead, hammer signing, holding up flames, etc. this works out just fine. If they choose to memorize the ceremony, this is easily done, but we can’t expect this of everyone. At the same time, the folk gain a higher level of participation. If the gothi or gythja sings or speaks a verse in Galdralag, the words of the blot are thus divided evenly, which make for a vibrant, powerful observance, in my opinion. I have often found that blotar written in prose tend to be a bit wordy, with mainly the gothi speaking, which sometimes can result in people losing some of their focus on the task at hand. The idea is to create an exciting, uplifting event that helps everyone in attendance achieve a bond with our pantheon and those around them. This system has been wonderful at achieving this for myself and those I have performed the blotar with.

Since I have started using the verses, I have noticed a dramatic difference in the flow and vibe of the rites I have partaken in, which is why I wanted to share this information with as many as possible. It is not my intent to devalue or disrespect anyone’s method of celebrating our ancient ways, merely to share my personal discoveries in the hopes to gain and offer as much knowledge and understanding of our faith as possible. In the end, the blotar we use are a matter of our own choices, our own decisions in forming a relationship with the Gods and Goddesses.

Hengest Thorsson

Hengest Thorsson